Have you ever wondered why American cities look the way they do? Why do sprawling suburbs dominate the landscape? Or why The Rent is Too Damn High? The answer, in many cases, lies in zoning.

Zoning, a seemingly mundane system of land-use regulations, has become contentious, attracting both fervent advocates and staunch critics. M. Nolan Gray's book Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It offers a scathing critique of zoning in the United States. Gray convincingly argues that zoning, despite its purported goals of order and efficiency, has actually undermined the very foundations of a thriving city. He posits that zoning has exacerbated the housing affordability crisis, restricted economic growth, and perpetuated racial and economic segregation.

Thanks in no small measure to zoning, millions of Americans struggle to make rent or mortgage payments…we are collectively less productive and innovative…our cities are still shockingly segregated, along both racial and economic lines. And one of the most powerful tools we have for combating climate change—building more walkable, energy-efficient, compact cities—is blocked off by zoning codes adopted nearly a century ago.

Where Zoning Came From: What It Is and How It Works

At its most basic, zoning is how the government regulates land use and building density on private property. It dictates what you can build, where you can build it, and how big it can be. Imagine a city meticulously divided into a colorful patchwork of districts on a map, each with its own rules. This is the zoning map, and it's the cornerstone of zoning. But the real meat of the matter is found in the accompanying zoning text, a dense and often bewildering document that spells out the specific regulations for each district.

Zoning emerged in the early 20th century from a desire to manage urban development, protect property values, and preserve “neighborhood character.” The Standard Zoning Enabling Act (SZEA) provided local governments with a ready-made framework for enacting zoning laws, facilitating the rapid spread of zoning across the country. With the SZEA and ongoing support from the federal government—especially under figures like Herbert Hoover—by 1936 zoning had been adopted by approximately 1,322 cities. Following World War II, federal agencies, such as The Federal Housing Administration, conditioned grants on the adoption of zoning such that by the 1970s, zoning was deeply entrenched in the American urban landscape.

Zoning describes a complex system of use and density controls.

Use Regulations: Zoning segregates cities into distinct districts dictating what kinds of businesses or activities are allowed. Districts typically fall into the categories of residential, commercial, and industrial. Want to open a bakery in a residential neighborhood? Zoning might have something to say about that.

Density Regulations: Zoning also controls how densely you can build within each district. This is where things get interesting (and complicated). Some common forms:

Explicit density regulations limit the number of dwelling units allowed on a lot. 75% of the country is zoned for single-family housing, which means an outright ban on multi-family housing. Where multi-family housing is permitted, there are often unit caps, for example, duplexes, triplexes, or apartment buildings with a maximum number of units.

Minimum lot sizes dictate the smallest area a single building can occupy, which lowers density by reducing the number of homes that can be built on a given land area.

Floor-area ratios are the ratio of a building's floor area to its lot size and thus limit the maximum amount of usable space that can be built on a given plot of land.

Setbacks dictate the distance a building must be set back from property lines, and like floor-area ratios, reduce the amount of usable space.

Minimum parking requirements require a certain amount of off-street parking per unit, which drives up costs and eats into the available land. (If you’re interested in parking, I wrote a post all about it!)

The High Cost of Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Hurts American Cities

Here are some of how zoning has had a devastating impact on American cities, pushing the American Dream further and further out of reach for millions:

The Affordability Crisis: Zoned Out of the Market

Zoning's most glaring failure has been its role in creating the housing affordability crisis that is gripping cities across the country. By artificially restricting the housing supply, zoning has driven up prices, making it increasingly difficult for people to find affordable places to live. Think of it like this: if you limit the number of apartments that can be built in a city experiencing rapid job growth, you're essentially creating a bidding war for a limited number of units. This drives up rents and home prices, forcing many people to either move to less desirable locations or spend an unsustainable portion of their income on housing. The consequences of this zoning-induced housing shortage are far-reaching, contributing to overcrowding, long commutes, and, in the worst cases, homelessness.

Economic Stagnation: Zoning Out Innovation

For the first time in history, Americans are systematically moving from high-productivity cities to low-productivity cities, in no small part because these are the only places where zoning allows housing to be built.

Gray argues that restrictive zoning policies, particularly in high-productivity cities, don't just make housing unaffordable; they also stifle economic growth and innovation on a national scale. By making it prohibitively expensive to live in these economic powerhouses, zoning prevents people from moving to areas where they could contribute the most to the economy. In aggregate, this also hinders the formation of economic clusters—those concentrations of specialized industries and talent that drive innovation and economic growth. When housing costs are artificially inflated, it becomes difficult for new businesses and startups to attract and retain the skilled workers they need to thrive, ultimately slowing down the pace of innovation.

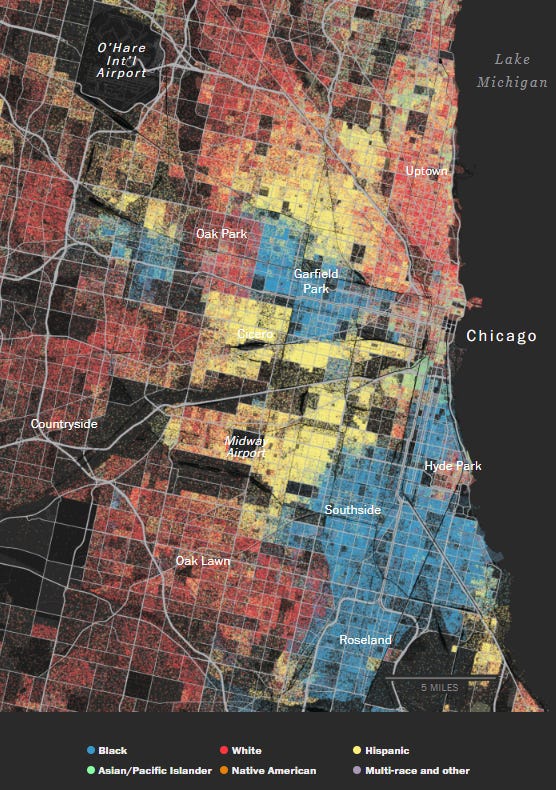

Racial and Economic Segregation: Apartheid by Design

While rarely acknowledged, zoning has played a central role in perpetuating racial and economic segregation in America. From its inception, zoning has been used to explicitly exclude racial minorities and low-income residents from desirable neighborhoods. In the early 20th century, this often took the form of explicitly racist zoning ordinances that prohibited certain groups from living in specific areas. While such blatant discrimination is no longer legal, its legacy endures, as zoning continues to be used to create and maintain segregated communities.

This segregation is achieved through various means:

Minimum Lot Sizes: Large minimum lot sizes in affluent neighborhoods effectively price out lower-income families who cannot afford to purchase large, expensive homes.

Bans on Multi-Family Housing: Prohibiting the construction of apartments and other multi-family housing in certain areas serves to limit housing options for lower-income residents, who are more likely to rent than own.

The combined result is that zoning reserves the best parts of every town for an elite few—not only the best housing, but also often the best school districts, the best public services, and the best access to jobs. And it shows up in the data, with basic quality of life metrics like life expectancy, lifetime earnings, and educational attainment varying dramatically from neighborhood to neighborhood and suburb to suburb. Zoning systematically locks our most vulnerable populations out of those neighborhoods and suburbs where they would be best positioned to find opportunity, both for themselves and for their children.

Mandating Sprawl

Zoning has played a significant role in shaping the sprawling, car-dependent landscape that defines much of America. By encouraging low-density development and discouraging walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, zoning has made it difficult to build sustainable, transit-oriented communities. Zoning causes sprawl through:

Single-Family Zoning: Zoning vast tracts of land for single-family homes forces cities to expand outwards, consuming valuable farmland and natural habitats, and contributing to habitat loss and climate change.

Parking Requirements: Mandating excessive off-street parking for new developments encourages car ownership and discourages walking, biking, and public transit.

Use Segregation: Separating residential, commercial, and industrial uses forces people to drive further for work, shopping, and other daily errands.

Fleeing Sustainability

Gray points out that despite its reputation for environmental consciousness, California's restrictive zoning policies are contributing to a less sustainable outcome on a national scale. California boasts some of the greenest cities in the country in terms of household carbon emissions, mainly due to the state's temperate climate, which reduces the need for energy-intensive heating and cooling. However, the lack of housing affordability is forcing people to move to less energy-efficient regions like the Sun Belt.

The Sun Belt, with its rapid population growth and sprawling development patterns, faces significant sustainability challenges. High energy consumption in cities like Phoenix, San Antonio, and Dallas is driven by the need for extensive air conditioning during hot summers and heating during cooler months. Even if these cities were to adopt more sustainable transportation and housing practices, their energy consumption would still exceed that of their Californian counterparts.

By pushing people out of sustainable cities and into less sustainable ones, zoning regulations are ultimately undermining national efforts to combat climate change. More housing construction in California's cities would enable more Americans to live in energy-efficient environments and reduce their carbon footprint. This, in turn, would make a greater contribution to national sustainability goals than hoping for technological advancements to make living in the Sun Belt less environmentally taxing.

In conclusion, zoning, despite its initial goals of order and efficiency, has had a far-reaching and detrimental impact on American cities. It has made housing unaffordable, restricted economic growth, perpetuated segregation, and fueled unsustainable sprawl. As we look toward the future, it's time to rethink this flawed system and explore alternative approaches to urban planning that prioritize affordability, equity, and sustainability.

The Great Unzoned City

Gray presents the case study of Houston, Texas, a city that has famously rejected zoning.

Houston is the fourth largest city in the US, boasts incredible population growth, and is now considered the most diverse city in the nation. But unlike cities burdened by restrictive zoning, Houston's housing market remains relatively affordable.

So how does Houston manage growth without relying on zoning?

Market Forces at Play: Land prices are a powerful signal that guides development. Where demand is high, prices rise, encouraging developers to build up and increase density. This results in a natural clustering of industries around transportation hubs, commercial centers along major corridors, and residential areas filling in the gaps. This market-driven approach has allowed Houston to adapt and evolve organically, responding to the needs and preferences of its residents.

Deed Restrictions: While Houston rejects city-wide zoning, it does utilize deed restrictions. These are private agreements among property owners that set rules for land use within specific neighborhoods or developments. Think of it as a hyper-local, opt-in form of zoning that empowers communities to choose the level of regulation that suits them. Though Gray isn’t pro-deed restrictions in theory, in practice he shows how they’ve been used as a compromise to keep homeowners who want more control over their immediate surroundings happy, while preventing them from dictating land use for the entire city.

Regulating Nuisances: Instead of the complicated system of use regulations found in zoning codes, Houston focuses on regulating specific activities that negatively impact residents, such as excessive noise, fire hazards, and development in floodplains. It also regulates uses that tend to bother people no matter where they're located like slaughterhouses, strip clubs, and billboards.

While Gray presents Houston as a paragon of what is possible without zoning to maintain affordability, it’s still sprawling and auto-centric. He points to the fact that they might not have a “zoning code” but still have parts of zoning, such as minimum parking requirements. Yet, private developers can’t single-handedly make a city walkable and transit-oriented. It requires a city-wide plan and government intervention to make a city fertile for dense and mixed-use development.

Rethinking Zoning

We've seen how zoning has wreaked havoc on American cities, making them unaffordable, stagnant, segregated, and sprawling. But it doesn't have to be this way. There's a growing movement to rethink this outdated system, with reformers pushing for both incremental changes and more radical overhauls. Let's take a look at some of the key strategies for fixing zoning:

Zoning Reform: Patching Up a Broken System

Many advocates are pushing for reforms that would make zoning less restrictive and more responsive to the needs of modern cities. Some of the most popular reforms include:

Legalizing "Missing Middle" Housing: One of the most contentious aspects of zoning is single-family zoning, which prohibits anything other than detached single-family homes on a given lot. Reformers are pushing to legalize "missing middle" housing types, such as duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings, in areas currently zoned for single-family homes only. This would allow cities to grow more densely and create more affordable housing options. Minneapolis is one city that has already taken this step, eliminating single-family zoning citywide.

Easing Restrictions on ADUs: Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) offer a way to add density without significantly altering the character of single-family neighborhoods. An ADU is a secondary housing unit located on a single-family residential lot, such as an apartment within a house, a converted garage, or a detached structure in the backyard. Cities can liberalize their ADU ordinances by removing barriers like minimum lot sizes, owner-occupancy requirements, and excessive parking mandates. California (and San Diego in particular) has been a leader in ADU reform, repeatedly preempting local restrictions to make it easier for homeowners to build ADUs. These state-level efforts aim to override local opposition and promote greater housing affordability.

Eliminating or Reducing Parking Minimums: Mandating a certain number of off-street parking spaces for new developments has contributed to sprawl, increased housing costs, and reduced walkability. Reformers are advocating for the elimination or reduction of parking minimums, allowing developers to determine the appropriate amount of parking based on market demand. Buffalo, New York, has become the first major U.S. city to eliminate parking minimums citywide.

State-Level Intervention: Recognizing the challenges of enacting meaningful reform at the local level, some states are taking steps to preempt local zoning restrictions that hinder housing affordability and economic growth. This can include setting statewide standards for things like minimum lot sizes, parking requirements, and ADU regulations, preventing local governments from enacting excessively restrictive policies. Arkansas, for example, in 2019 passed a law preventing local governments from legislating the aesthetics of houses.

These reforms represent important steps toward creating more functional, affordable, and equitable cities. However, the question remains: is reform enough, or is it time to abolish zoning altogether?

A Post-Zoning World: Reimagining Urban Planning

While these reforms are positive steps, Gray argues they don't go far enough. Zoning, he says, is fundamentally flawed and incapable of achieving its stated goals. So what does Gray think land-use regulation and urban planning will look like in a post-zoning world?

Nuisance-Based Regulations: Instead of relying on the blunt instrument of use separation, cities could focus on regulating the specific impacts of different uses. This might involve setting clear standards for things like noise, pollution, and traffic, ensuring that new developments don't impose undue burdens on their neighbors. Yet, many cities already have nuisance-based regulations that are often not enforced. If cities are already failing to enforce these regulations, what would change in a post-zoning world? Gray suggests that planners, freed from managing zoning, would have more time to devote to developing and enforcing these regulations.

Mediation and Community Agreements: Gray suggests that instead of trying to resolve every conflict through a priori rules, planners should embrace their role as mediators. Planners could play a more active role in facilitating agreements between communities and developers, helping to resolve land-use conflicts through negotiation and compromise. While mediation is a valuable tool, it relies on the willingness of parties to compromise. What happens when parties are entrenched in their positions and refuse to budge? Gray doesn't address the limitations of mediation or suggest alternative strategies for resolving intractable disputes.

Reviving Physical Planning: Beyond regulating nuisances, planners could also focus on proactively shaping the physical environment to create more livable and sustainable communities. This would involve investing in public infrastructure, such as parks, schools, and transportation systems, and creating comprehensive plans that guide growth in a more rational and equitable direction.

While Gray makes a strong argument for abolishing zoning - it’s actively harmful and isn’t even effective at regulating incompatible uses or preventing nuisances as it claims to do – he doesn’t make a compelling case for how we’d address them better in the future. He claims that without zoning, they would have so much more time to effectively use these other tools that they already have in their toolbelts – enforcement, mediation, and master planning. While I’m skeptical, I’m not a city planner, so maybe I don’t appreciate the sheer amount of time that zoning takes up in their jobs. And even if this were the case, are these strategies sufficient or are there other tools and processes that can be implemented to make planning more effective?

In “Arbitrary Lines,” Gray convincingly demonstrates that zoning has failed to achieve its intended goals. Instead, it has created a host of unintended consequences that negatively impact American cities. The system's rigidity has strangled housing affordability, driven economic stagnation, and exacerbated racial and socioeconomic disparities.

While some cities are attempting to ameliorate these issues through reforms like ADU legalization and parking requirement reductions, Gray contends that these measures are mere bandages on a fundamentally broken system.

He posits that zoning's inherent flaws necessitate a paradigm shift in how we approach urban planning, advocating for a future where cities prioritize affordability, equity, and sustainability. This future demands a shift in the role of planners, moving away from enforcing arbitrary lines to mediating between stakeholders and promoting a more holistic approach to urban development. While his ideas about a post-zoning world aren’t fully fleshed out, it’s clear that we need to put an end to zoning.